Getting CodeQL CLI Running on an M1 Mac & Diving Into a Reflected XSS Query for Go

I’ve been working on getting CodeQL up and running on my Macbook M1 Air and had some initial issues so I decided it could be helpful to document how I got a successful CodeQL query running using the CodeQL CLI.

Starting Out

Install CodeQL using Brew by running the following command:

brew install --cask codeql

From there, pick a CodeQL query you want to test out from the official repository on GitHub. I went with the Reflected XSS query for Go which can be found here. The following files can be pulled from the folder:

ReflectedXss.ql - The CodeQL query

ReflectedXss.go - The code example that is unsafe

ReflectedXssGood.go - The code example that is safe

Within that Go directory on GitHub you’ll also find a file called “qlpack.yml”. Download it and insert it into a folder along with the files mentioned above. The logic for the files above is that the “Good” file is one that query shouldn’t match on, whereas the regular “ReflectedXss.go” file is the one it should match on.

Once your directory is created with the above files you can create a CodeQL database with the following command:

codeql database create <database-name> --language=go

Getting Packs Set Up

CodeQL queries will require certain dependencies. These can be seen reflected in the “qlpack.yml” file. For this query these are:

codeql/go-all

codeql/suite-helpers

codeql/util

The file may also contain the “${workspace}“ string which will need to be changed. Run the following command to download and install each of these dependencies:

codeql pack download codeql/<Dependency Name>

From there, navigate to the folder of your CodeQL’s dependcy located here:

/Users/<your name>/.codeql/packages/codeql/<package>

From there you’ll see a folder with the version information. Alter the “qlpack.yml” file to contain that version information. Also use it to install the package using the below command:

codeql pack install /Users/<your name>/.codeql/packages/codeql/go-all/<version number>

Here is what my “qlpack.yml” looks like:

name: codeql/go-queries

version: 0.7.10-dev

groups:

- go

- queries

suites: codeql-suites

extractor: go

defaultSuiteFile: codeql-suites/go-code-scanning.qls

dependencies:

codeql/go-all: 0.7.9

codeql/suite-helpers: 0.7.9

codeql/util: 0.2.9

warnOnImplicitThis: true

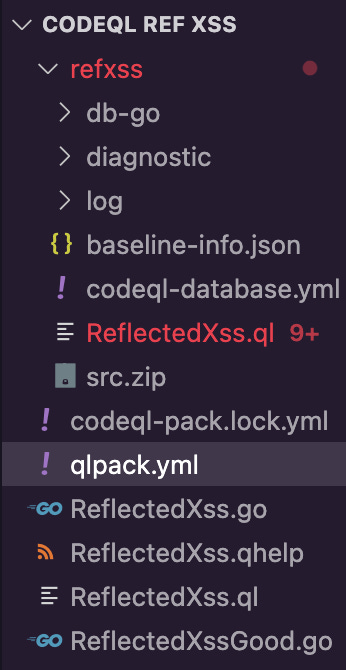

With all of that, you should be ready to rock. Here’s a view of my file structure — just for reference:

Running the Query

Drop the .ql query file into folder with the .go program in it for it to be the sole query being run. From there you can execute the following command from the same directory of the Go code:

codeql query run ReflectedXss.ql --database=<database name>

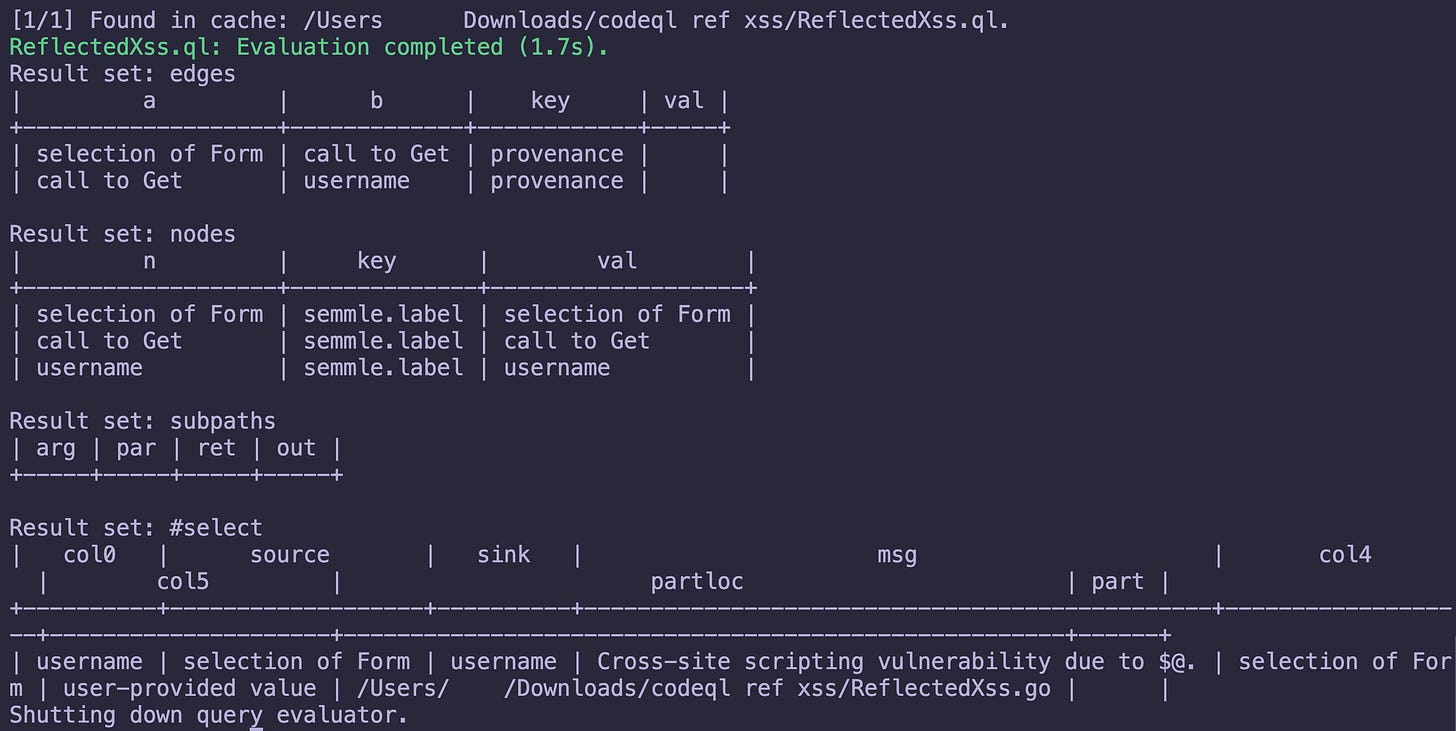

A successful hit will look like this:

Boom! Success! If you’ve reached this point everything should be good-to-go (ha!). If you want to see what an unsuccessful hit looks like comments out the affected area in the Go program, recreate the database, then re-run the CodeQL query like this:

Then recreate the CodeQL DB by running the command below.

codeql database create refxss --language=go --overwrite

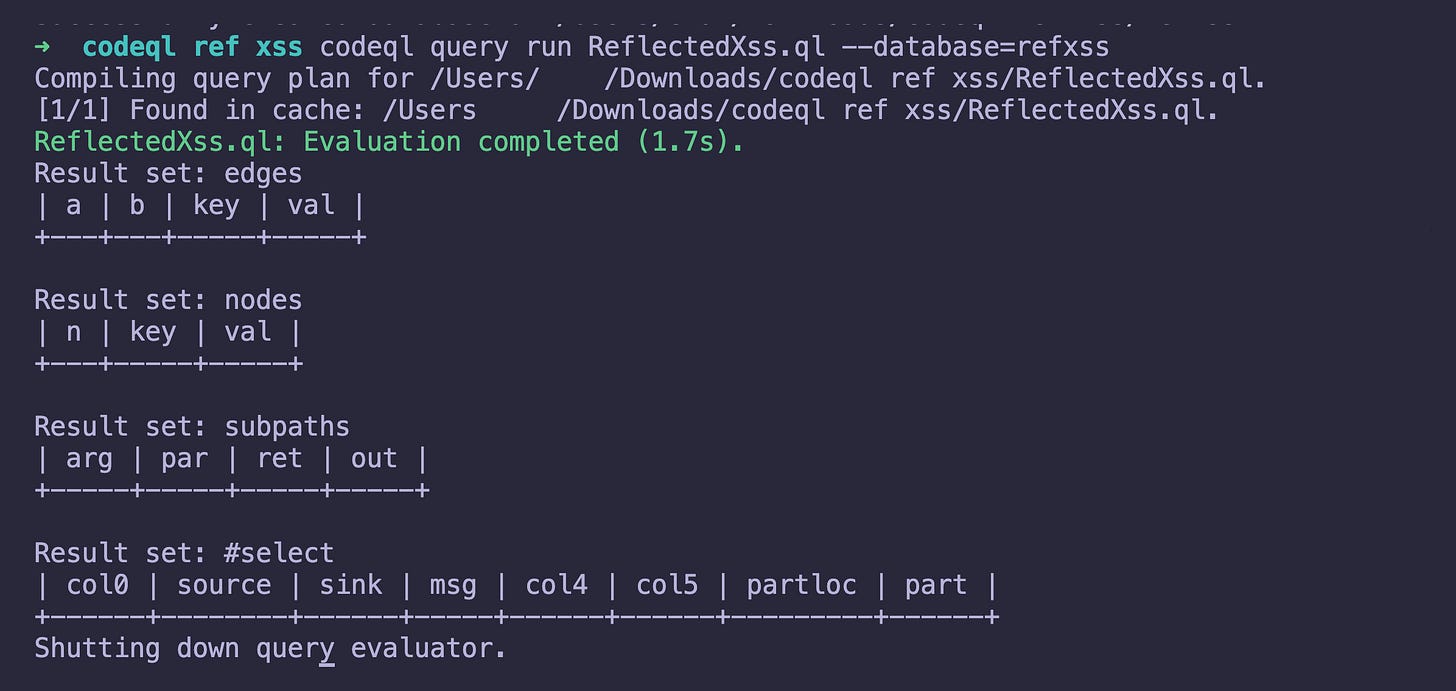

And execute it by re-running the previously mentioned command for queries. An unsuccessful hit will look like this:

Digging Into the Query

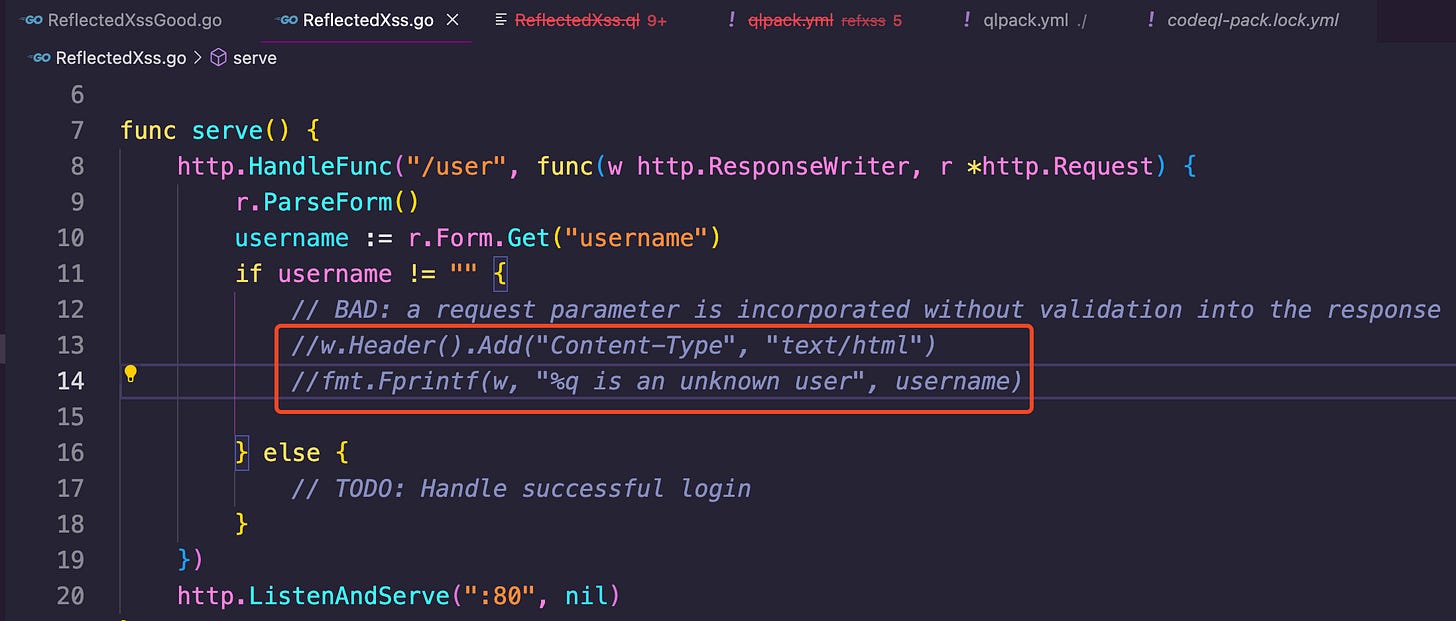

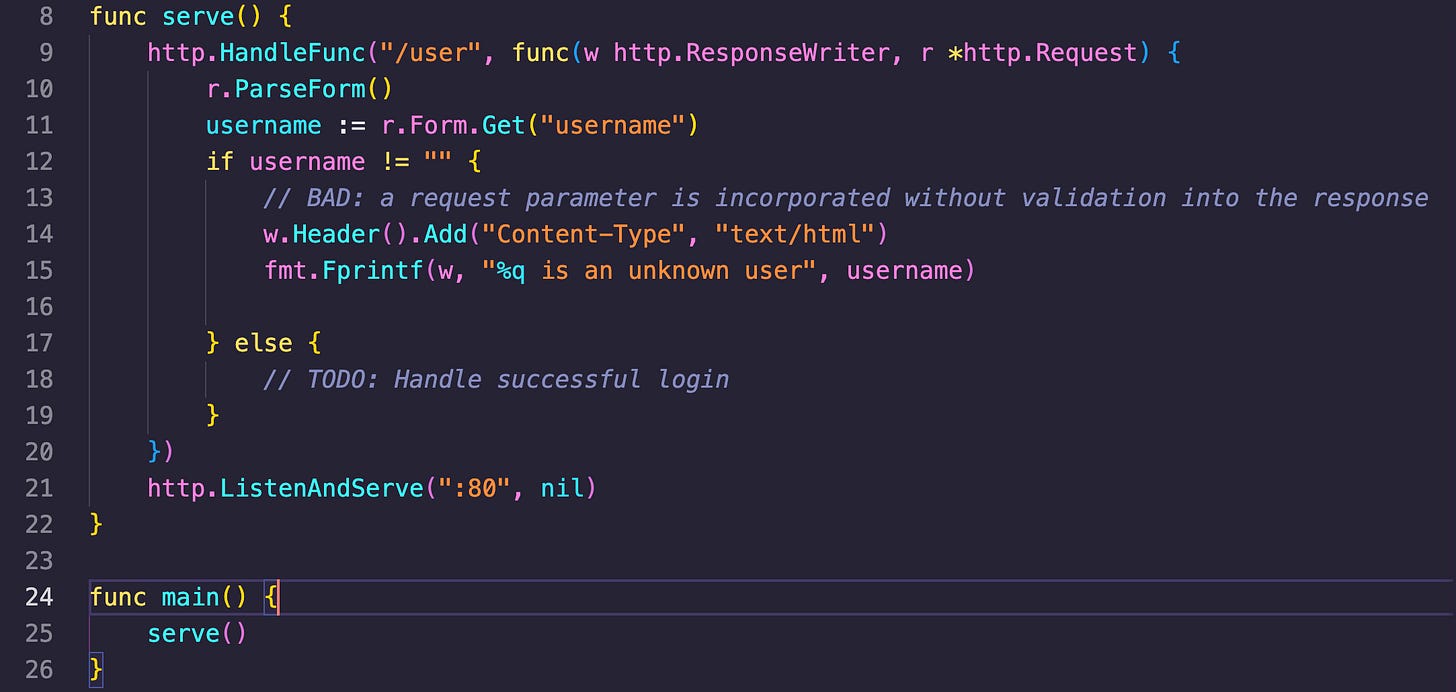

This is the current code I have in the “ReflectedXss.go” file that gets a hit from the CodeQL query:

And then the current CodeQL query is:

I’m EXTREMELY new to CodeQL, and past reading the docs I’ve always found just Googling around and experimenting to be the best way to learn something new (for myself). So line by line, I want to go through and see EXACTLY what is going here. Feel free to skip this if you were just looking for notes on how CodeQL is installed and ran.

Exploring Imports

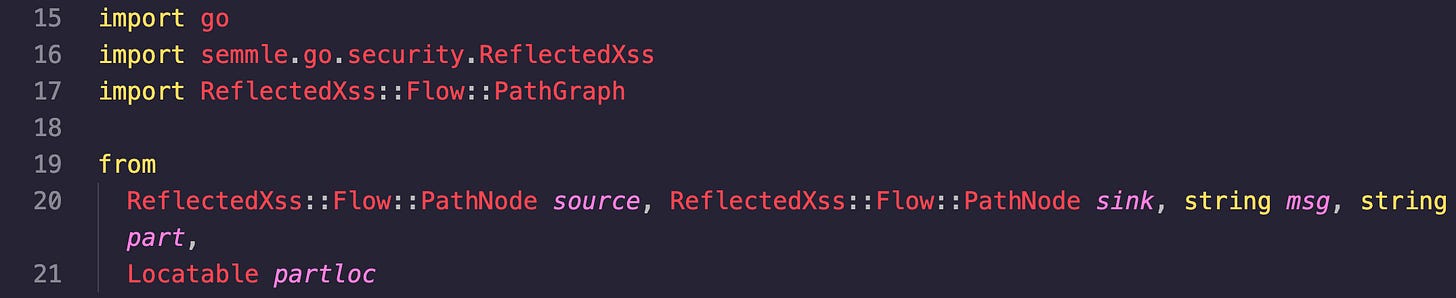

At the top there are three imports:

go

semmle.go.security.ReflectedXss

ReflectedXss::Flow::PathGraph

The first one, “import go”, is bringing in the specific CodeQL library meant for analyzing Go. This is pretty in-depth, and a great explanation of it can be read here. Every step I take into CodeQL I realize just how absolutely gigantic the ecosystem is, and how much there is to learn here. GitHub has also created an index for API documentation for “codeql/go-all” that can be found here.

The second one, “import semmle.go.security.ReflectedXss” has a .qll file that can be seen here. It helps nail down data flow from user input to sinks.

Last, the “import ReflectedXss::Flow::PathGraph” imports the “PathGraph” module from the “ReflectedXss::Flow” namespace, enabling the use of the “PathNode” class which represents nodes in the data flow path. It also has the “flowPath” predicate which identifies data flow paths between source nodes (user input) and sink nodes (potential XSS vulnerabilities).

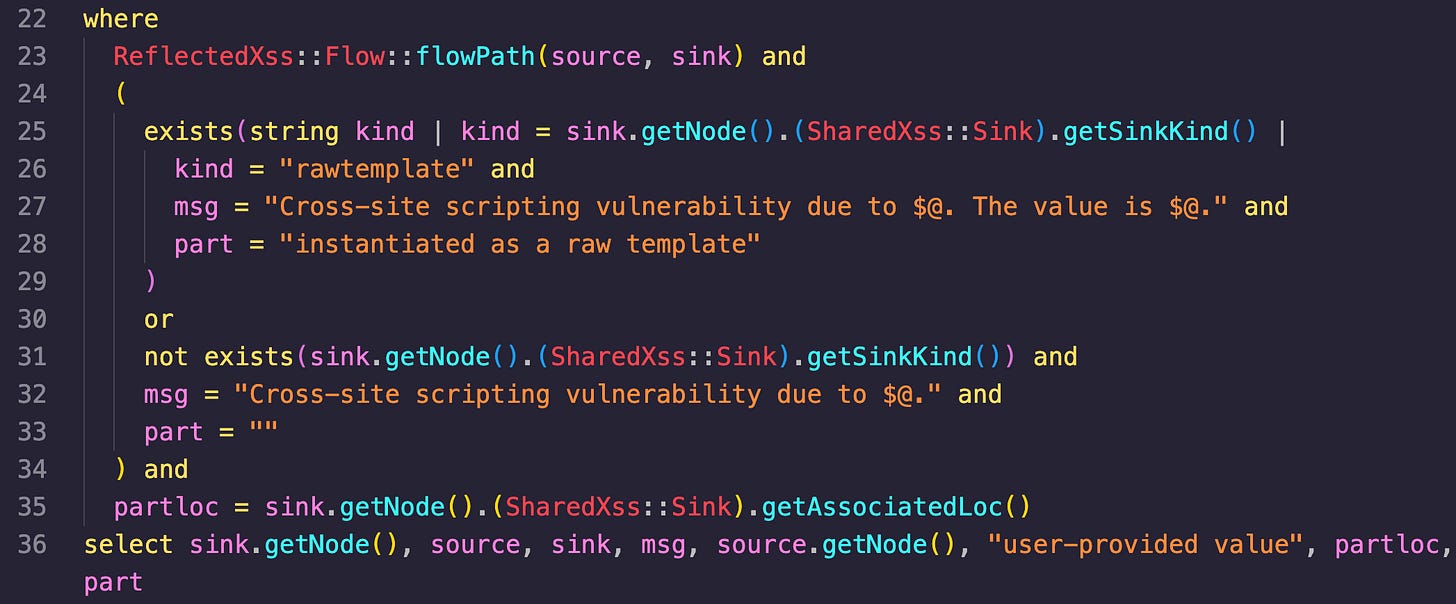

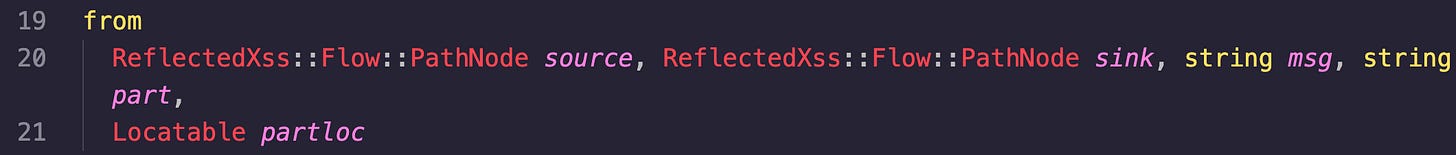

from

When I said line-by-line I meant LINE-BY-LINE. Let’s go!

The “ReflectedXss::Flow::PathNode source” section is declaring “source” the variable of the type “ReflectedXss::Flow::PathNode”. This represents the source node of where the user-input originates, and is a part of the data flow path.

The next one is similar, but it is declaring sink the same type. It represents where the XSS vulnerability potentially would be, AKA where user input is incorporated into an HTTP response.

The “string msg” and “string part” lines will just be used to add more context if a vulnerability is found.

The last part declares the variable “partloc” of the type “Locatable”. The “Locatable” class represents a location in the source code (line or column). “partloc” will be used to store the location of the vulnerable sink node.

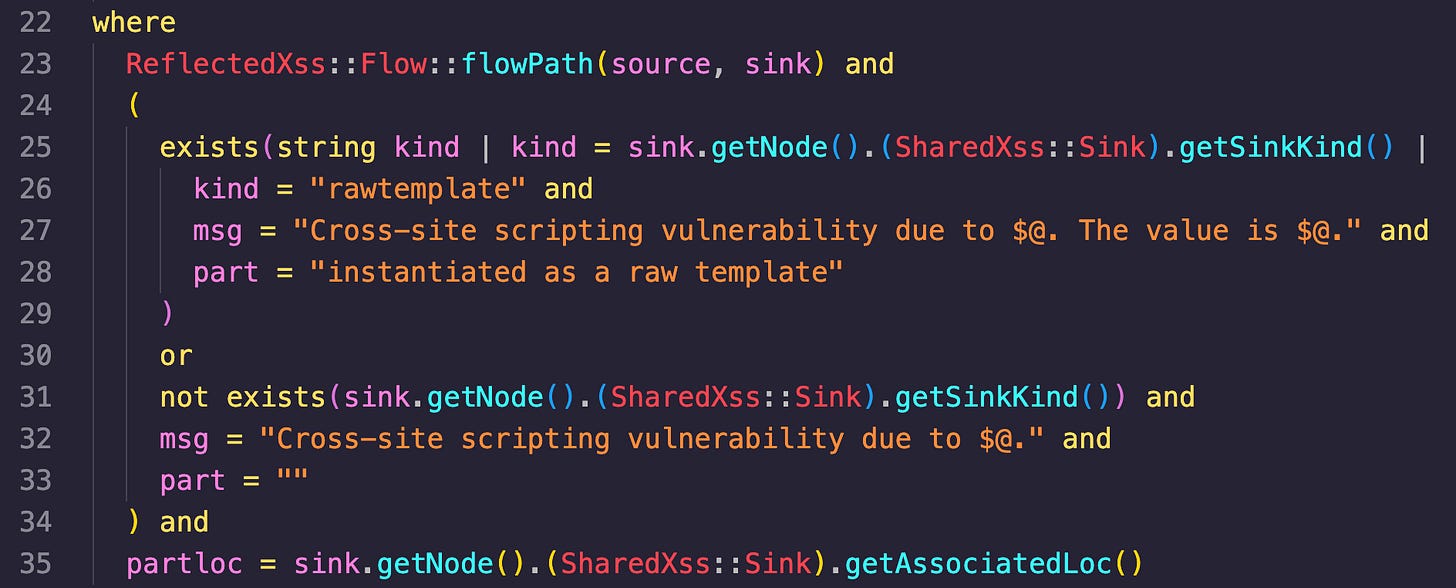

where

This section is used to specify the conditions that must be true for a query to return successfully and contain all of the information that was setup beforehand (like the source, sink, msg, etc).

Line 23 checks if there is a valid data flow path from the source node to the sink node. The “flowpath” predicate contains the logic for identifying the these data flow paths.

Line 25 checks if there is a specific kind vulnerable sink node. The variable “kind” is declared and several steps are taken. The “getSinkKind()” predicate is called on the “SharedXss::Sink“ class, which represents a potential XSS vulnerability.

Line 26, if the “kind” is “rawtemplate” the “msg” and “part” variables are set to the specific messages outlined on lines 27 and 28.

The “not exists” section starting on line 31 handles the case where there isn’t a specific kind returned by “getSinkKind()”. It will set the “msg” variable to a more generic message and the “part” variable to an empty string.

On line 35 the location associated with the sink node is retrieved by calling the “getAssociatedLoc()” predicate on the “SharedXss::Sink” class. This location is then assigned to the “partloc” value.

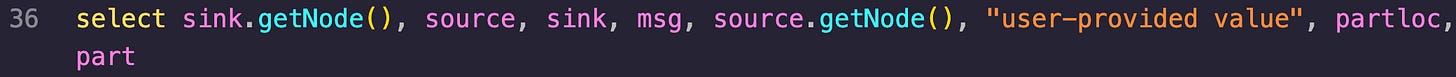

select

Last but not least, there’s the select clause. This is used to specify the information that is used in the query’s output. I’m going to break these down a little more since it’s just one big line of commas.

sink.getNode() - This selects the node object representing the sink node (AKA the potential XSS vulnerability location) from the “sink” variable of type “ReflectedXss::Flow::PathNode”

source - This selects the entire source variable of type “ReflectedXss::Flow::PathNode”. It represents the source node where the user input originates.

sink - Similar to the above except it represents the sink node where the potential XSS vulnerability is.

msg - The message describing the potential XSS vulnerability.

source.getNode() - This selects the node object representing the source node (AKA where the user input originates) from the “source” variable of type “ReflectedXss::Flow::PathNode”.

“user-provided value” - This is included for context, it’s a string literal.

partloc - Represents the location associated with the sink node.

part - This can contain an additional message that has more context on the vulnerability.

What About the Semmle ReflectedXss.qll File?

Don’t worry! I was wondering about it as well. As a reminder, this is the one that was imported at the top of the previous query. Since its being imported I wanted to see what it was really about. It can be accessed here, and hopefully I’ll have some extra time to step through it in the near future and see how far back I need to go analyzing the imported modules to understand the query from the top to the bottom.